Rashod Taylor at Obscura Gallery

Published May 21, 2022

Interview by Jean Dykstra for Photograph Magazine, AIPAD Photography Show Edition

Like many first-time fathers, Rashod Taylor began taking photographs of his son, LJ, when he was born. Eventually, though, he began to think there might be more to the photographs than family snapshots, and he began gently choreographing his (mostly) cooperative son in images that lovingly portray mundane moments from his life. The photographs, which sometimes include Taylor himself or his wife, are tender, intimate images of a Black family raising a Black boy in the United States. “It’s challenging,” says Taylor. Works from the series Little Black Boy are on view at Obscura Gallery’s booth at the AIPAD Photography Show, along with wet-plate collodion images from his series My America.

photograph: How did the series Little Black Boy get started?

Rashod Taylor: I had made pictures of my son for a while. I shot in film, and I’d look at the contact sheets, and I thought the work had something that other people could connect to. Being a Black man raising a Black boy today is challenging, and around this time, I thought about Tamir Rice, who was shot and killed by police, and George Floyd, and all of that made me want to use these images to say something a little bit more.

photograph: They’re beautiful images, and they have the detail and clarity that come from working with a 4×5 view camera. And they are images of tenderness and affection between a father and son, which we don’t see that much.

Taylor: People of color are often portrayed in the opposite light. For me it was important to give a spotlight to what that looks like – the tenderness and love, and how myself and my wife care for our son.

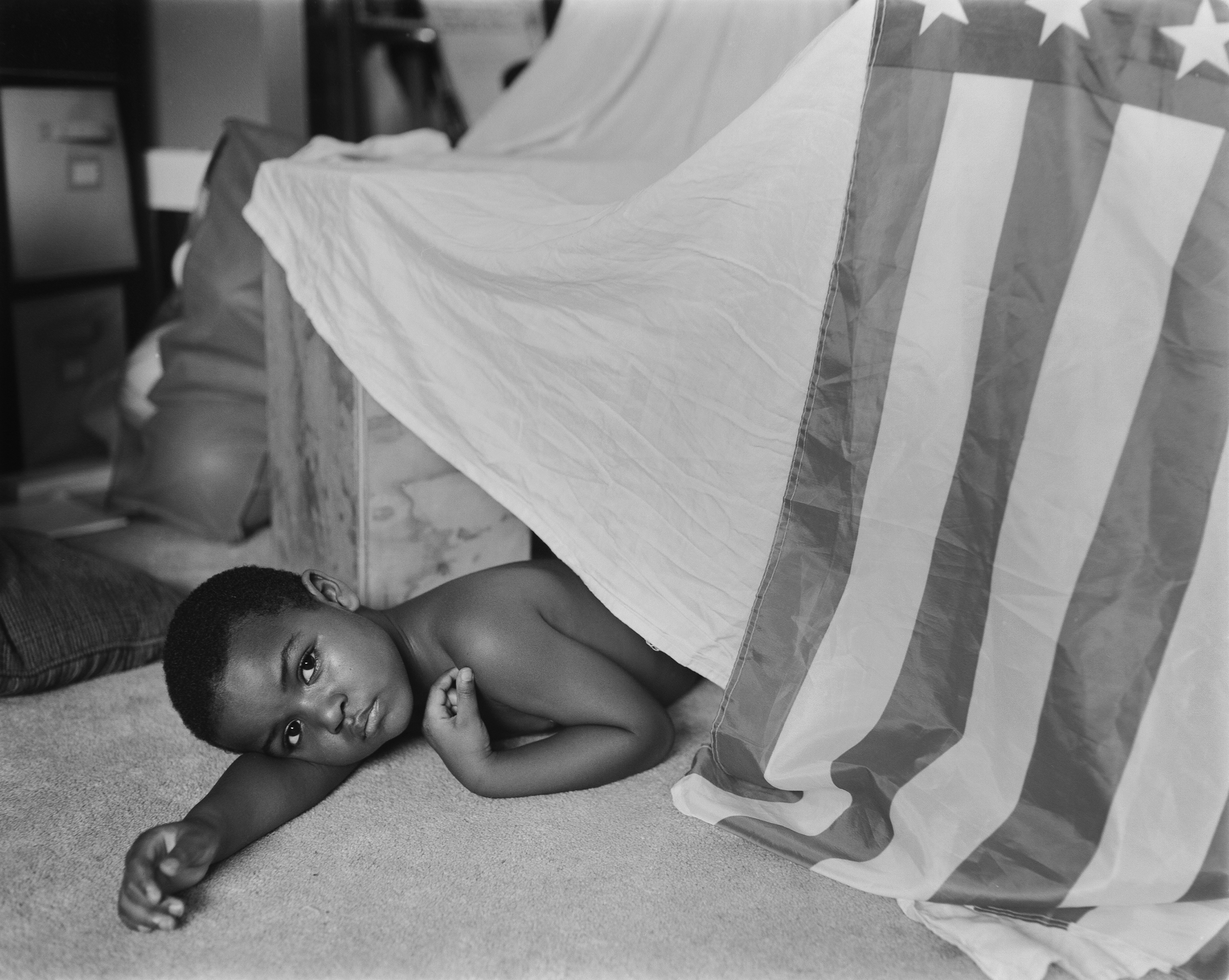

Rashod Taylor, LJ and His Fort, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Obscura Gallery

photograph: You’ve talked about the influence of Sally Mann. Are there other photographers who’ve influenced your work?

Taylor: Sally Mann is the most prominent photographer that focused on her family for so much of her career. Those images just looked so effortless, but she used an 8×10 view camera, so that’s even more of a labor of love. I like the humanity of Gordon Parks, how he talks about letting his pictures be his weapons against poverty and racism. I really take that to heart. I want people to engage with these images in a way that gets the conversation started: How come we don’t see more images of Black boys or Black girls being lifted up?

photograph: Was there a point where you began envisioning the photographs as something more than family photographs, as a project that engaged with themes of racial inequality and social justice and became part of that conversation?

Taylor: There’s a picture of LJ wearing a t-shirt that says Dream Big, but he also had a police officer badge on, and then in the background was this little white girl, and her back is to him. There’s so much going on in that image. A lightbulb kind of went off, and I thought: I think I might have something here.

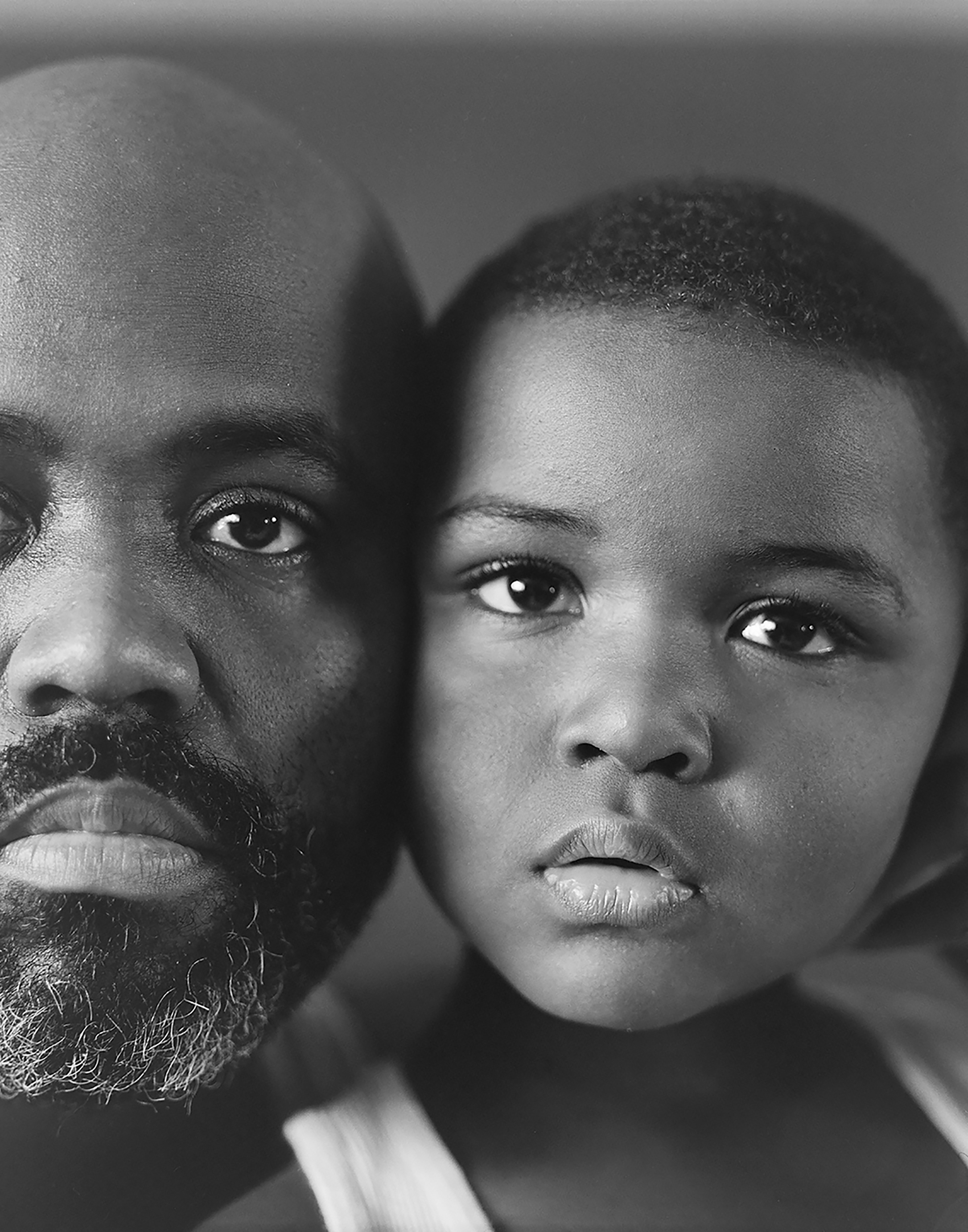

Rashod Taylor, Tired of Fighting, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Obscura Gallery

photograph: Can you talk about your series My America? What made you decide to use the wet-plate collodion process, which is so labor intensive?

Taylor: I got into wet plate about 10 years ago. I was getting burnt out with digital and wanted to get back to making tangible work with my hands. I saw some work by Joni Sternbach, and I really loved that. Then I took a workshop with Dale Bernstein, and I really I gravitated toward the process. I also enjoy history; understanding that this was the second photographic process after daguerreotypes, and looking at Civil War images and images of families, there wasn’t much representing Black people. It was expensive, and they couldn’t afford it. The few images of Black people were from the war. It was an interesting time: Black people were allowed to fight even though they had no rights. And that’s a theme in American history since then, into World War II, and Vietnam a little bit. So that was an interesting thread, and I love the fact that the wet plate dates back that far.

Rashod Taylor, The Past, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Obscura Gallery

Rashod Taylor, The Past, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Obscura Gallery